Records of Life celebrates the use of paper to document and record our lives in a variety of ways. Whether it’s a quick note to remind one of errands to be done, more thoughtful journaling, or collecting quotes or recipes, these unintentional records shape impressions of our society for future generations to come.

Paper researcher and salesman Harrison Elliott documented his life in notebooks and letters, and disseminated thoughts in researched articles. He created keepsake booklets of his work, and then shared these pieces with fellow researchers.

The portion of his collection at the Paper Museum represents

-

Records of Thought: his private, interior thoughts, intended for an audience of one—the author.

-

Records of Relationship: handmade paper samples and letters to friends and colleagues, intended for a select few to read.

-

Records of Practice: the research, articles, and pamphlets created for consumption by a public audience.

Much of this ephemera was never intended to be preserved. This unintentional history reveals how people think and process information. The everyday bits of life fill in the pieces of what is important to the writer.

As you view this exhibit, consider the many ways you consciously and unconsciously document the days of your life and the things that inspire you.

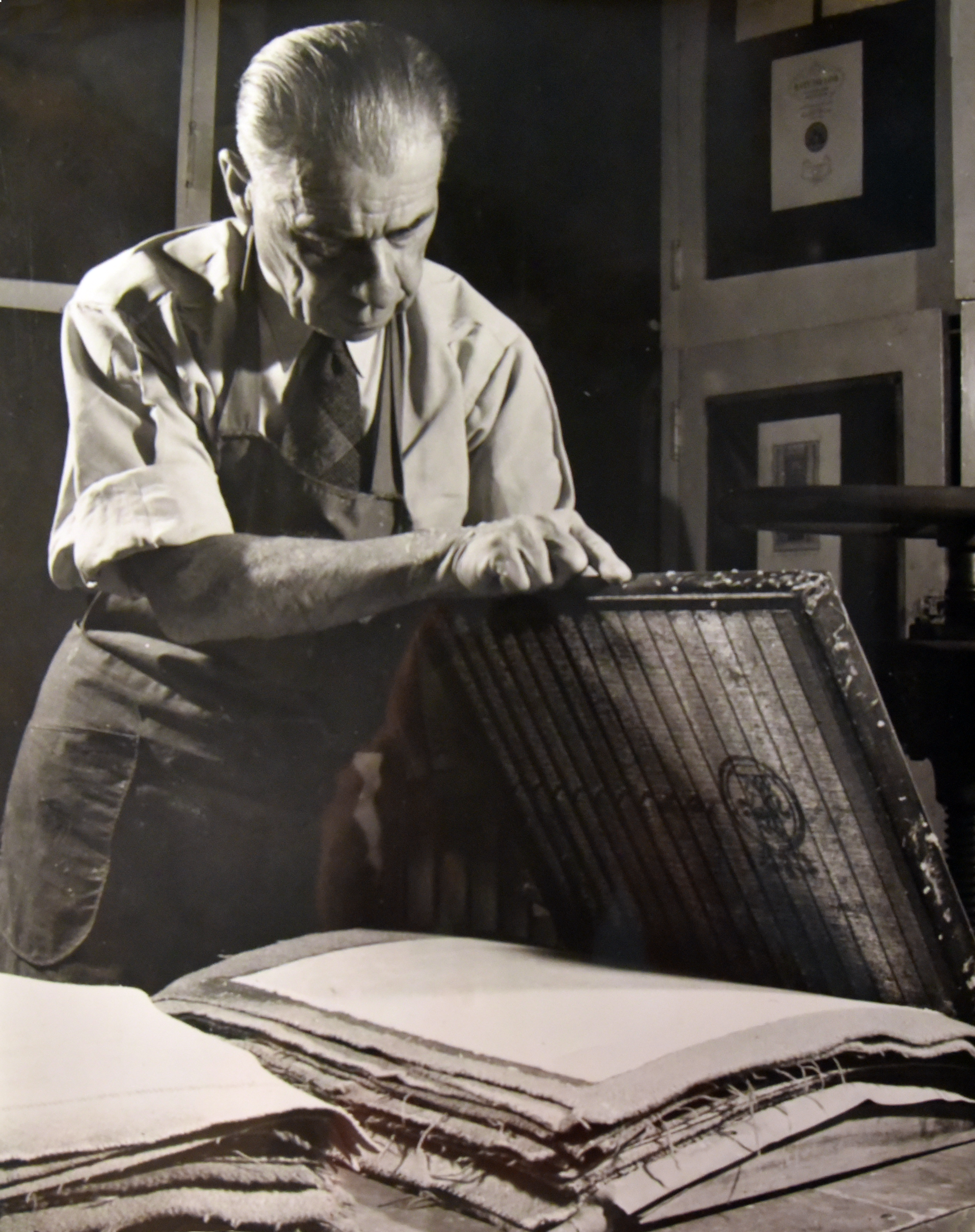

Harrison Elliott (1879 - 1954)

Harrison Elliott was a man of paper, and a man of words about paper. He recorded his thoughts in notebooks for himself, letters to colleagues, and articles for the public.

His career in paper began in 1903 at International Paper, eventually becoming head of the mail order department. In 1925, he joined the Japan Paper Company as the advertising and direct mail promotions manager. The company imported fine papers from Japan and Europe. In 1951, Elliott

retired from the paper industry, but continued to immerse himself in the world of paper.

Elliott did more than work for and promote the paper industry. He began collecting paper in 1914 and wrote extensively about his research in industry publications. He also developed long relationships with other paper researchers, including Paper Museum founder Dard Hunter. In 1932, Elliott began making paper on a small scale. He made paper for books, prints, broadsides, and other uses. He also gave talks and demonstrations about papermaking, using miniature-scale machinery in the process.

He married in his fifties, and his wife, Blanche, passed away in 1944. They had no children. Elliott was reported by friends and co-workers to be quiet and reserved. Elliott’s organization and humor come through in his writings—for himself, and for others.

Elliott lived most of his life in New York. In 1953 he was featured in an exhibit, Rags to Handmade Paper, along with paper innovator Douglass Howell. In early 1954 he moved to Arlington, VA to be closer to his sister. A man of words, he donated collections of his works to the Library of Congress, art collections to the Smithsonian, paper samples to Columbia University and the New York Public Library, and ephemera to the Paper Museum.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

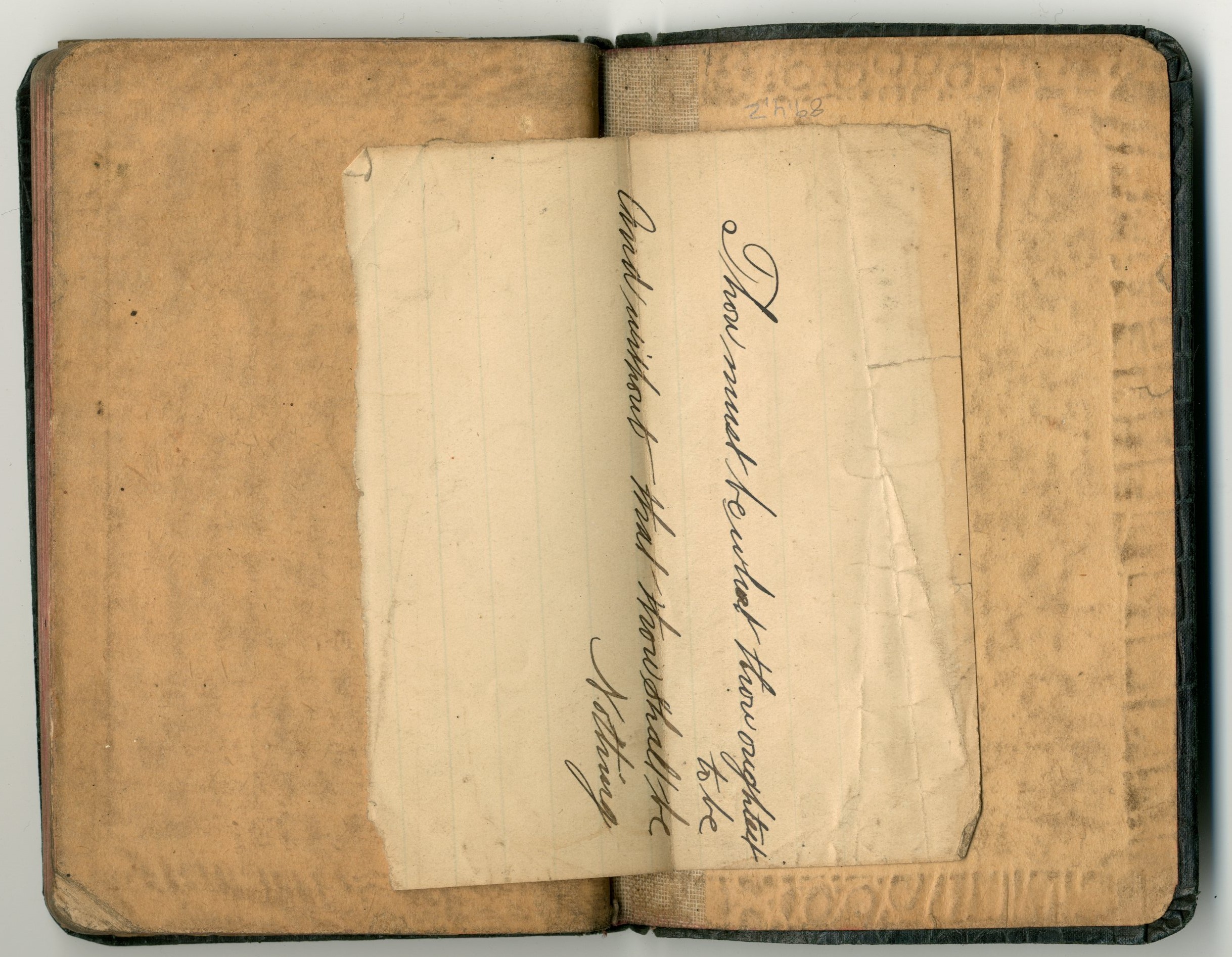

Records of Thought:

Records of Thought explore the private, interior musings of the mind. These may be daily journals, daybooks, and notebooks containing everything from grocery lists next to an interesting quote or notes to be remembered.

Harrison Elliott’s notebooks included everything from facts about paper history, quotes from magazines, possible marketing phrases, recipes for papermaking, jokes, and packing lists. At times the juxtaposition of these disjointed topics created passages akin to poetry:

Catches the eye and makes a

Good impression

Embellish the paper

Facilitate and cheapen the production

- Harrison Elliott, notebook “Bronxville 7078” ca. 1941

Diaries and journals have long histories as primary sources, revealing daily activities and inner thoughts. Many diaries and journals are meant for personal use: to keep track of activities or to make sense of life. The process of recording requires some sort of organization, even if it’s only understood by the writer. Materials like Elliott’s notebooks reveal thoughts and ideas in a different way than a diary or journal. These notebooks represent an unfiltered recording of thought.

Records of thought can be mysterious: why did the author write down a particular thought? What does an abbreviation mean? Did a plan come to fruition?

With the advent of devices like Palm Pilots and apps like EverNote, how has the way you track information changed?

Do you keep a diary? How would you feel if someone read it?

Would a device like a FitBit be classified as a Record of Thought? Why or why not?

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

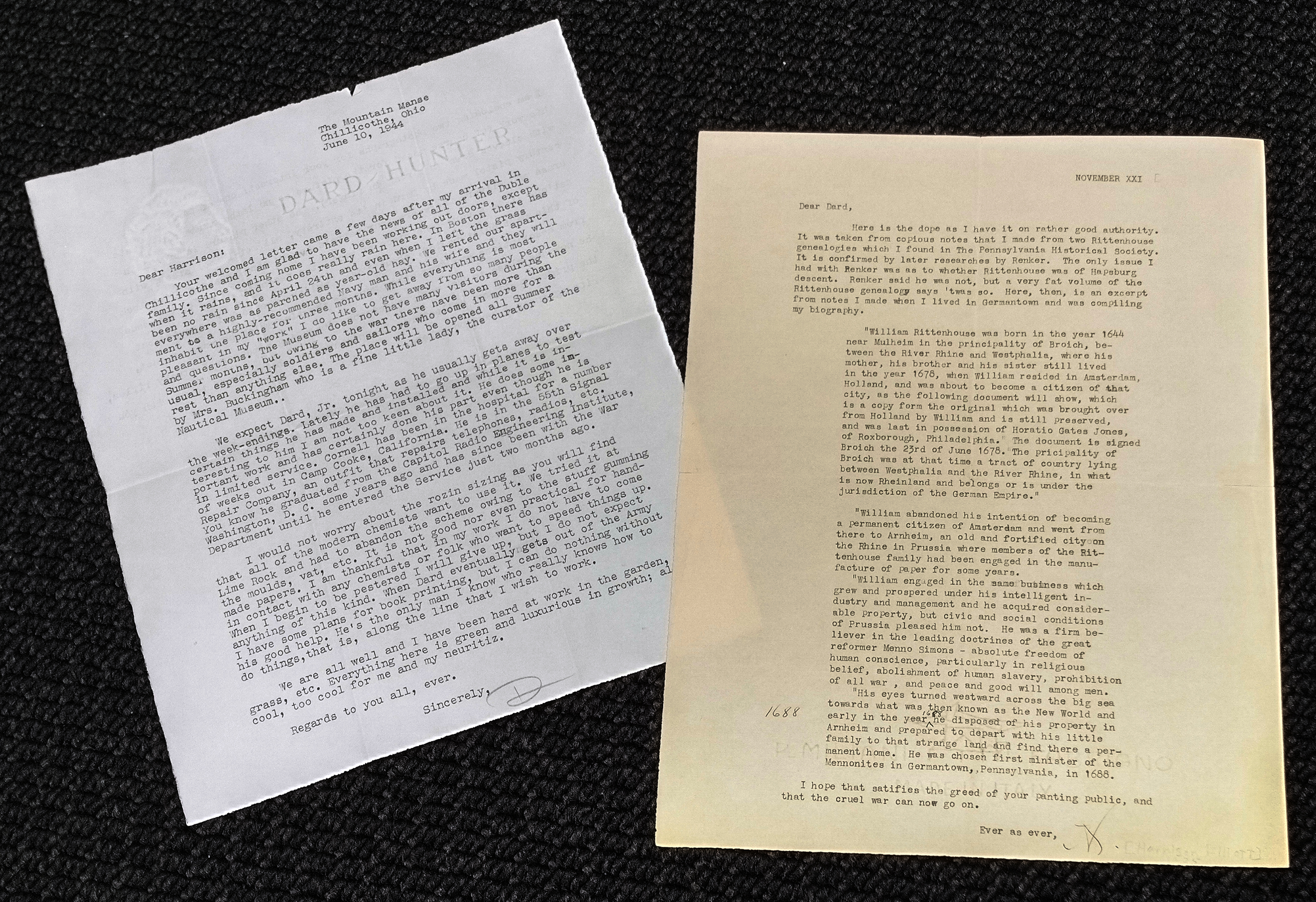

Records of Relationship:

While “records of thought” are designed solely for the writer and “records of process” are created for a wide range of viewers, “records of relationship” are intended for a small audience—the writer and the recipient. These documents are written conversations between only a few people; they are most commonly expressed in the form of letters and cards.

As someone who lived in the pre-digital era, Harrison Elliott depended on the written word to communicate with his far-flung network of friends and colleagues. Conversations happened

slowly, over a period of weeks and months, rather than instant communication. Written records like these reveal the mundane and the philosophical.

Letters provide insight to historians. They can reveal state of mind through the content of the words, or how the letter is written—is it typed? Is it scrawled on a card? The familiarity and relationship with the recipient emerges in a letter, illustrated by the salutation and sign-off, along with the style of the content.

Records of relationship provide insight into communication between two or more parties. The full relationship is not always revealed, and more questions may be raised for later readers.

What is the last letter you received?

With the rise of texting and instant messaging, which are not saved in a physical form, how will future historians understand interpersonal relationships?

What are examples of “records of relationships” that aren’t letters or cards?

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Records of Practice

Records of Practice look outward to a larger, exterior audience. Examples include travel logs or marginalia designed to be a conversation between the notetaker and future readers. Everything from collective recipe books to scholarly journals represents this form of record. Specialized publications by industry or to increase knowledge in a field are some of the best-known records of practice.

Harrison Elliott researched paper history and experimented with many papermaking techniques and paper crafts. He shared the knowledge he acquired from these activities in articles written for industry journals, historic societies, and paper enthusiasts. Not only were these articles published, Elliott often bound copies of his articles into small pamphlets covered in his own handmade paper. These polished, published articles are the finished product of the thoughts gathered in the many notebooks and letters written by Elliott.

Today, records of practice take the form of how-to blogs, vlogs, Twitter, and other social media posts. Sometimes they are informal, technical notes shared between groups of people with similar interests on specific topics. While specialized publications continue to be important, the democratization of access to information can greatly expand understanding by the general public and non-specialists.

Records of practice demonstrate the how and why of a subject. They provide a roadmap of process and show where experiments were successful or failed.

What are advantages to publishing in specialized sources?

What are the disadvantages?

When you are looking for expert information on a subject, where do you look?

How do you know if the source is reliable?

With more content moving to locations like YouTube or TikTok, how to do you

think this affects access? Accuracy?

(text and background only visible when logged in)