The Birth of Papermaking

AD 105 is often cited as the year in which papermaking was invented. In that year, historical records show that the invention of paper was reported to the Chinese Emperor by Ts'ai Lun, an official of the Imperial Court. Recent archaeological investigations, however, place the actual invention of papermaking some 200 years earlier. Ancient paper pieces from the Xuanquanzhi ruins of Dunhuang in China's northwest Gansu province apparently were made during the period of Emperor Wu who reigned between 140 BC and 86 BC. Whether or not Ts'ai Lun was the actual inventor of paper, he deserves the place of honor he has been given in Chinese history for his role in developing a material that revolutionized his country.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Early Papermaking in China

Early Chinese paper appears to have been made by from a suspension of hemp waste in water, washed, soaked, and beaten to a pulp with a wooden mallet. A paper mold, probably a sieve of coarsely woven cloth stretched in a four-sided bamboo frame, was used to dip up the fiber slurry from the vat and hold it for drying. Eventually, tree bark, bamboo, and other plant fibers were used in addition to hemp.

The first real advance in papermaking came with the development of a smooth material for the mold covering, which made it possible for the papermaker to free the newly formed sheet and reuse the mold immediately. This covering was made from thin strips of rounded bamboo stitched or laced together with silk, flax, or animal hairs. Other Chinese improvements in papermaking include the use of starch as a sizing material and the use of a yellow dye which doubled as an insect repellent for manuscript paper.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Papermaking Spreads Throughout Asia

From China, papermaking moved to Korea, where production of paper began as early as the 6th century AD. Pulp was prepared from the fibers of hemp, rattan, mulberry, bamboo, rice straw, and seaweed. According to tradition, a Korean monk named Don-cho brought papermaking to Japan by sharing his knowledge at the Imperial Palace in approximately AD 610, sixty years after Buddhism was introduced in Japan. The Japanese first used paper only for official records and documentation, but with the rise of Buddhism, demand for paper grew rapidly.

Taught by Chinese papermakers, Tibetans began to make their own paper as a replacement for their traditional writing materials. The shape of Tibetan paper books still reflects the long, narrow format of the original palm-leaf books. Chinese papermakers also spread their craft into Central Asia and Persia, from which it was later introduced into India by traders. The first recorded use of paper in Samarkand dates from a battle in Turkestan, where skilled Chinese artisans were taken prisoner and forced to make paper for their captors.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

The Spreading of Papermaking in Europe

From Samarkand, papermaking spread to Baghdad in the 8th century AD and into Damascus, Egypt, and Morocco by the 10th century. Many Chinese materials were not available to Middle Eastern papermakers, who instead used flax and other substitute fibers, as well as a human-powered triphammer to prepare the pulp.

It took nearly 500 years for papermaking to reach Europe from Samarkand. Although the export of paper from the Middle East to Byzantium and other parts of Europe began in the 10th and 11th centuries, the craft was apparently not established in Spain and Italy until the 12th century. Early paper was at first disfavored by the Christian world as a manifestation of Moslem culture, and a 1221 decree from Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II declared all official documents written on paper to be invalid. (The interests of wealthy European landowners in sheep and cattle for parchment and vellum may also have exerted some influence.) The rise of the printing press in the mid 1400's, however, soon changed European attitudes toward paper.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

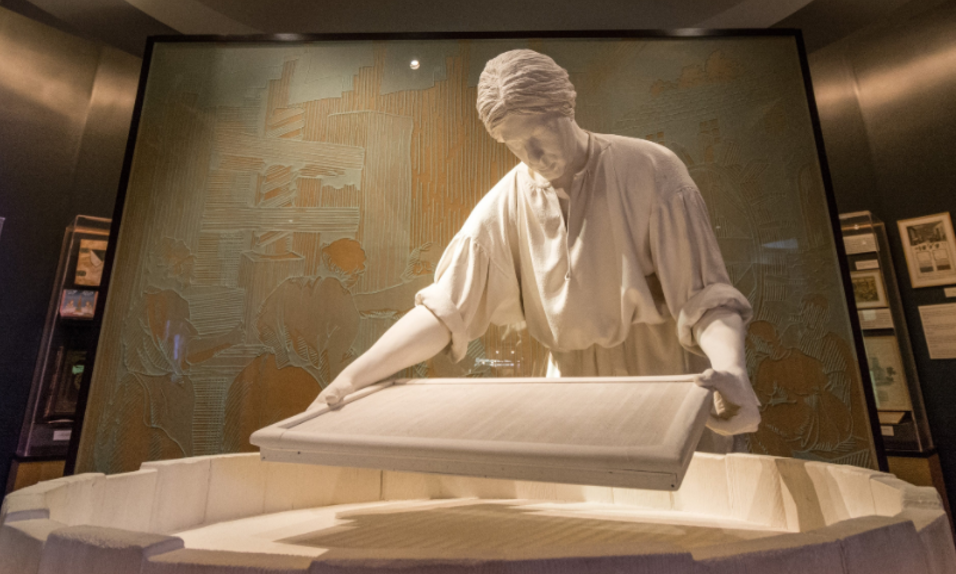

The Papermaker

This life-size statue, which stands in the center of the Paper Museum, is an adaptation of an illustration entitled "The Papermaker," which is believed to have first appeared in 1698 in the Book of Trades by Christopher Weigel. It next appeared in 1717 in the Book of Trades by Abraham van St. Clara, a copy of which is held by the Museum. The reproduction on which the statue is based appears on page 43 of Dard Hunter's book Papermaking Through Eighteen Centuries (New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1930), which is also on display in the Museum. In all its forms, "The Papermaker" is an excellent introduction to the craft of papermaking in pre-industrial Europe.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

The Process of Papermaking

Although the craftsman depicted in our statue would hardly recognize the equipment of a modern paper mill, the procedures he used to make paper were not that different from the processes of today. Preparing the stock, forming the paper web, drying the sheet, and applying coatings and additives were all as much a part of his work as they are of ours. Although many improvements in technology were made after the introduction of papermaking to Europe, the following description will give some impression of the operations which made up the papermaker's craft.

Raw Materials for Paper

The material of choice for the European papermaker was cotton or linen fiber from rags. The rags were sorted, cleaned, and heated in a solution of alkali, at first in an open vat and later under steam pressure. After draining and seasoning, the rags were then washed and macerated to a pulp, which was then bleached to remove the final traces of dyes and the residual darkening from the cooking process.

Paper Molds

To form a sheet of paper, the papermaker dipped a paper mold into the vat of stock and lifted it out horizontally, trapping the fibers against the screen of the mold. Paper molds were made by hand from parallel lengths of wire laced together together with fine wire or thread ("laid" molds) or from woven wire mesh ("wove" molds).

Drying the Sheet

After forming, the sheet was removed ("couched") from the mold and placed on felts or woolen cloth for pressing. A stack of paper sheets and felts, called a "post," was placed in a large wooden screw press, and all the workers in the mill were summoned to tighten the press by pushing or pulling a long wooden lever. An average 2-foot post might be reduced to 6 or 8 inches in this way.

After pressing, the sheets were strong enough to be lifted from the felts and hung to dry, usually in groups of four or five known as "spurs" to prevent wrinkling and curling. Drying was usually carried out in the highest level of the mill, away from soot and dust.

Sizing and Finishing

To make the paper less absorbent, the dried sheet was dipped in animal gelatin or glue. Such sizing was more important for writing papers than for printing stock, since printing inks were thicker and did not soak into the paper so easily. The first method for smoothing the sheet was simply to burnish each sheet by hand with a glossy stone; a water-powered hammer smoother was developed in the early 17th century.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)